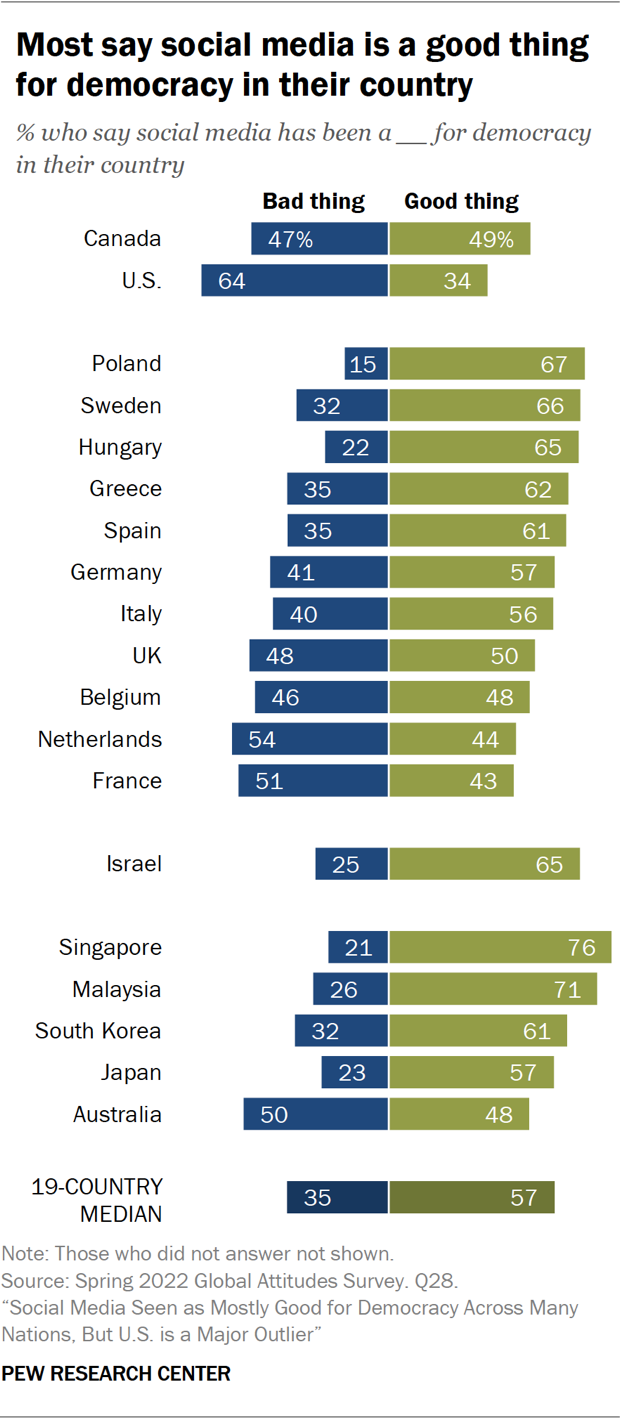

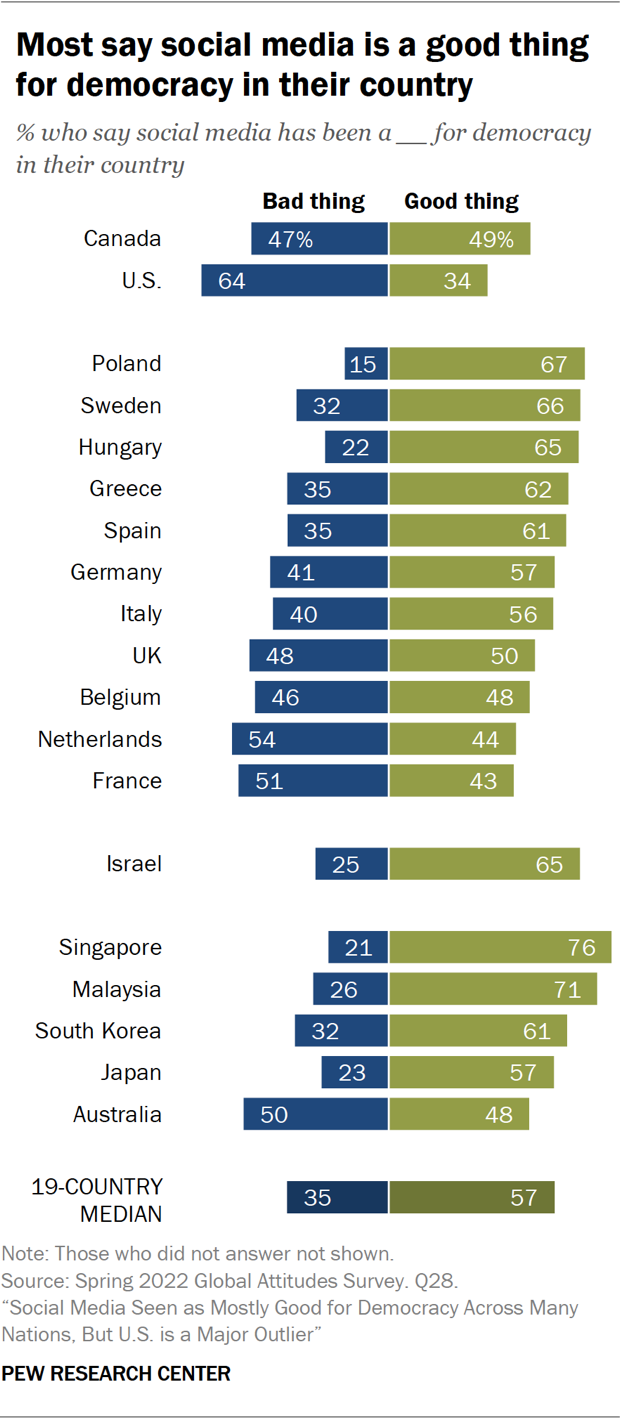

When asked whether social media is a good or bad thing for democracy in their country, a median of 57% across 19 countries say that it is a good thing. In almost every country, close to half or more say this, with the sentiment most common in Singapore, where roughly three-quarters believe social media is a good thing for democracy in their country. However, in the Netherlands and France, about four-in-ten agree. And in the U.S., only around a third think social media is positive for democracy – the smallest share among all 19 countries surveyed.

In eight countries, those who believe that the political system in their country allows them to have an influence on politics are also more likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy. This gap is most evident in Belgium, where 62% of those who feel their political system allows them to have a say in politics also say that social media is a good thing for democracy in their country, compared with 44% among those who say that their political system does not allow them much influence on politics.

Those who view the spread of false information online as a major threat to their country are less likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy, compared with those who view the spread of misinformation online as either a minor threat or not a threat at all. This is most clearly observed in the Netherlands, where only four-in-ten (39%) among those who see the spread of false information online as a major threat say that social media has been a good thing for democracy in their country, as opposed to the nearly six-in-ten (57%) among those who do not consider the spread of misinformation online to be a threat who say the same. This pattern is evident in eight other countries as well.

Views also vary by age. Older adults in 12 countries are less likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy in their country when compared to their younger counterparts. In Japan, France, Israel, Hungary, the UK and Australia, the gap between the youngest and oldest age groups is at least 20 percentage points and ranges as high as 41 points in Poland, where nearly nine-in-ten (87%) younger adults say that social media has been a good thing for democracy in the country and only 46% of adults over 50 say the same.

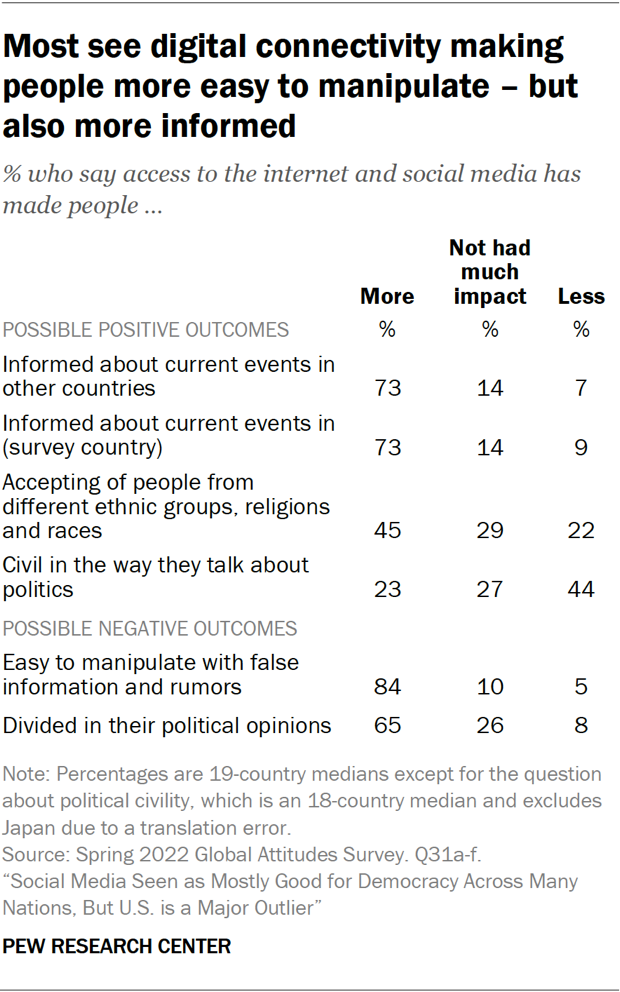

The publics surveyed believe the internet and social media are affecting societies. Across the six issues tested, few tend to say they see no changes due to increased connectivity – instead seeing things changing both positively and negatively – and often both at the same time.

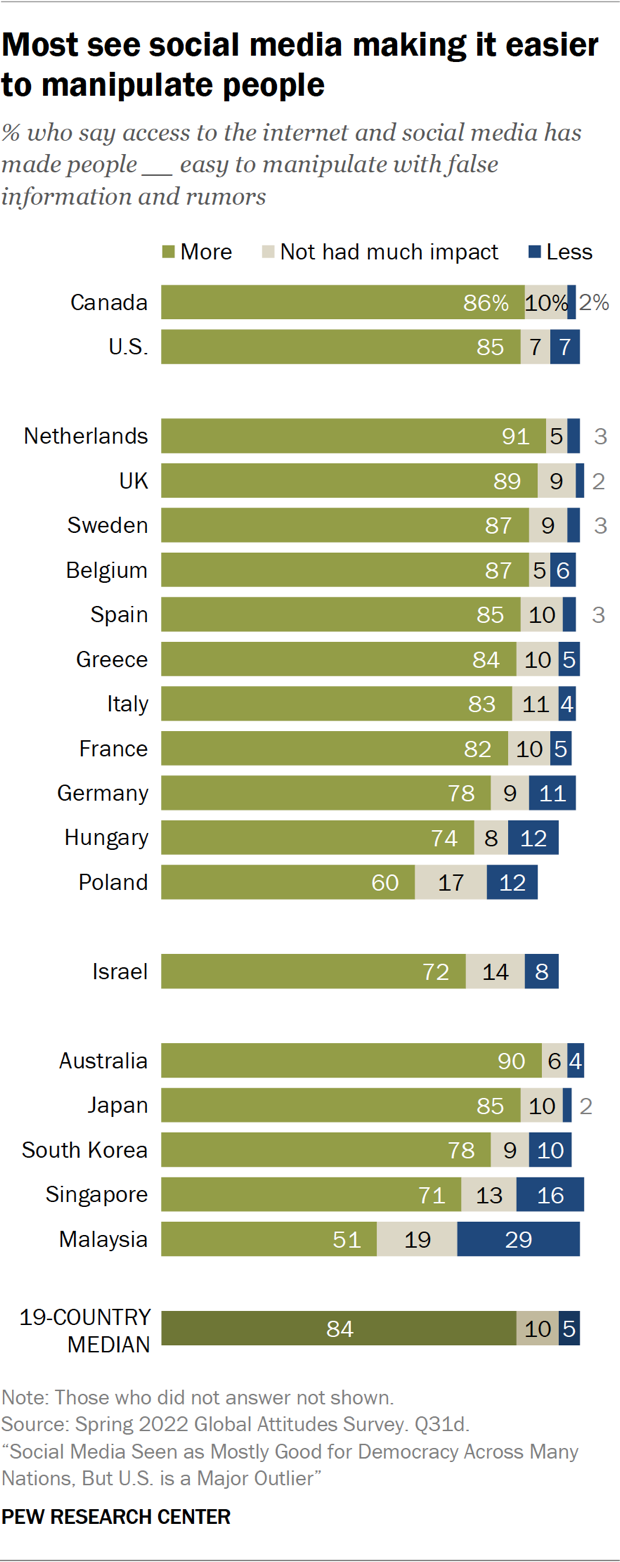

A median of 84% say technological connectivity has made people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors – the most among the six issues tested. Despite this, medians of 73% describe people being more informed about both current events in other countries and about events in their own country. Indeed, in most countries, those who think social media has made it easier to manipulate people with misinformation and rumors are also more likely to think that social media has made people more informed.

When it comes to politics, the internet and social media are generally seen as disruptive, with a median of 65% saying that people are now more divided in their political opinions. Some of this may be due to the sense – shared by a median of 44% across the 19 countries – that access to the internet and social media has led people to be less civil in the way they talk about politics. Despite this, slightly more people (a median of 45%) still say connectivity has made people more accepting of people from different ethnic groups, religions and races than say it has made people less accepting (22%) or had no effect (29%).

Previously reported results indicate that a median of 70% across the 19 countries surveyed believe that the spread of false information online is a major threat to their country. In places like Canada, Germany and Malaysia, more people name this as a threat than say the same of any of the other issues asked about.

This sense of threat is related to the widespread belief that people today are now easier to manipulate with false information and rumors thanks to the internet and social media. Around half or more in every country surveyed shares this view. And in places like the Netherlands, Australia and the UK, around nine-in-ten see people as more manipulable.

In many places, younger people – who tend to be more likely to use social media (for more on usage, see Chapter 3) – are also more likely to say it makes people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors. For example, in South Korea, 90% of those under age 30 say social media makes people easier to manipulate, compared with 65% of those 50 and older. (Interestingly, U.S.-focused research has found older adults are more likely to share misinformation than younger ones.) People with more education are also often more likely than those with less education to say that social media has led to people being easier to manipulate.

In 2018, when Pew Research Center asked a similar question about whether access to mobile phones, the internet and social media has made people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors, the results were largely similar. Across the 11 emerging economies surveyed as part of that project, at least half in every country thought this was the case and in many places, around three-quarters or more saw this as an issue. Large shares in many places were also specifically concerned that people in their country might be manipulated by domestic politicians. For more on how the two surveys compare, see “In advanced and emerging economies, similar views on how social media affects democracy and society.”

Misinformation has long been seen as a source of concern for Americans. In 2016, for example, in the wake of the U.S. presidential election, 64% of U.S. adults thought completely made-up news had caused a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current events. At the time, around a third felt that they often encountered political news online that was completely made up and another half said they often encountered news that was not fully accurate. Moreover, about a quarter (23%) said they had shared such stories – whether knowingly or not.

When asked in 2019 who was the cause of made-up news, Americans largely singled out two groups of people: political leaders (57%) and activists (53%). Fewer placed blame on journalists (36%), foreign actors (35%) or the public (26%). A large majority of Americans that year (82%) also described themselves as either “very” or “somewhat” concerned about the potential impact of made-up news on the 2020 presidential election. People who followed political and election news more closely and those with higher levels of political knowledge also tended to be more concerned.

Among adult American Twitter users in 2021, in particular, there was widespread concern about misinformation: 53% said inaccurate or misleading information is a major problem on the platform and 33% reported seeing a lot of that type of content when using the site.

As of 2021, around half (48%) of Americans thought the government should take steps to restrict false information, even if it meant losing freedom to access and publish content – a share that had increased somewhat substantially since 2018, when 39% felt the same.

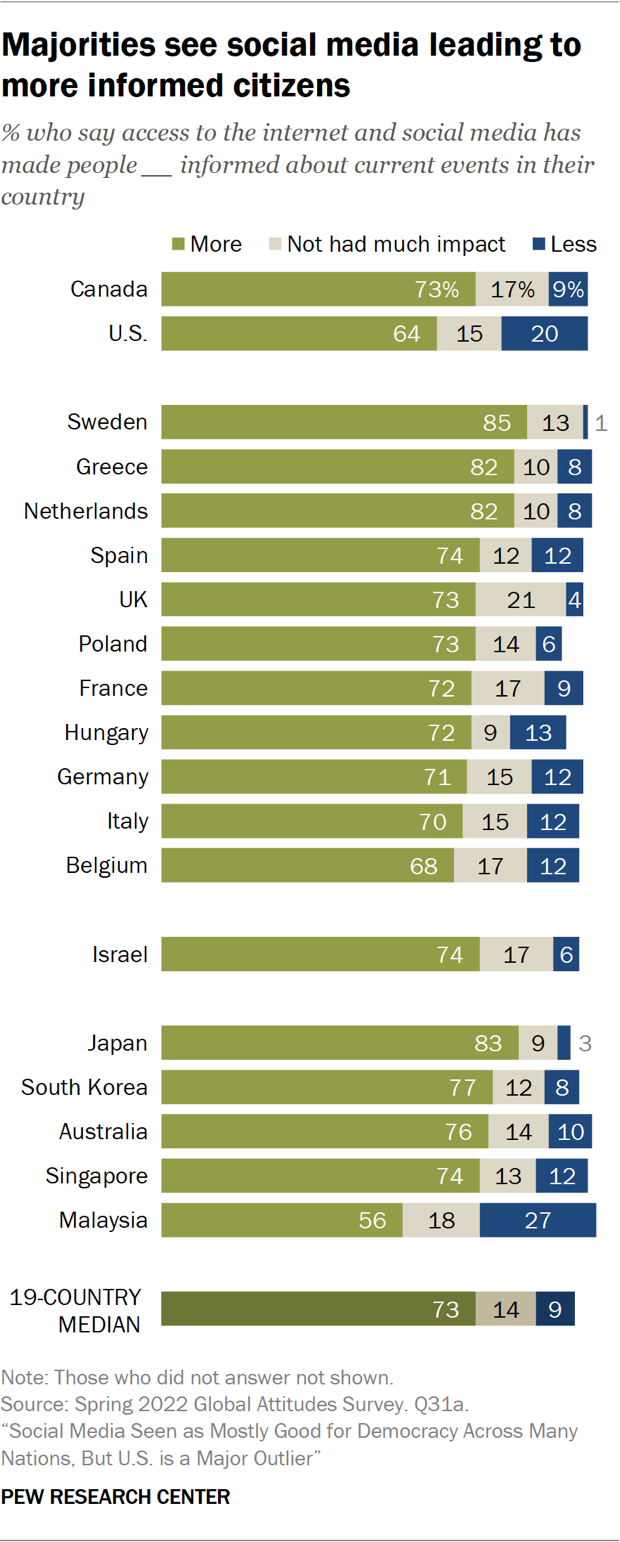

A majority in every country surveyed thinks that access to the internet and social media has made people in their country more informed about domestic current events. In Sweden, Japan, Greece and the Netherlands, around eight-in-ten or more share this view, while in Malaysia, a smaller majority (56%) says the same.

Younger adults tend to see social media making people more informed than older adults do. Older adults, for their part, don’t necessarily see the internet and social media making people less informed about what’s happening in their country; rather, they’re somewhat more likely to describe these platforms as having little effect on people’s information levels. In the case of the U.S., for example, 71% of adults under 30 say social media has made people more informed about current events in the U.S., compared with 60% of those ages 50 and older. But those ages 50 and older are about twice as likely to say social media has not had much impact on how informed people are compared with those under 30: 19% vs. 11%, respectively.

In seven of the surveyed countries, people with higher levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels to see social media informing the public on current events in their own country.

Majorities in every country also agree that the internet and social media are making people more informed about current events happening in other countries. The two questions are extremely highly correlated (r = 0.94), meaning that in most places where people say social media is making people more informed about domestic events, they also say the same of international events. (See the topline for detailed results for both questions, by country.)

In the 2018 survey of emerging economies, results of a slightly different question also found that a majority in every country – and around seven-in-ten or more in most places – said people were more informed thanks to social media, the internet and smartphones, rather than less.

In some countries, those who think social media has made it easier to manipulate people with misinformation and rumors are also more likely to think that social media has made people more informed. This finding, too, was similar in the 2018 11-country study of emerging economies: Generally speaking, individuals who are most attuned to the potential benefits technology can bring to the political domain are also the ones most anxious about the possible harms.

In the U.S., around half of adults say they either get news often (17%) or sometimes (33%) from social media. When it comes to where Americans regularly get news on social media, Facebook outpaces all other social media sites. Roughly a third of U.S. adults (31%) say they regularly get news from Facebook. While Twitter is only used by about three-in-ten U.S. adults (27%), about half of its users (53%) turn to the site to regularly get news there. And a quarter of U.S. adults regularly get news from YouTube, while smaller shares get news from Instagram (13%), TikTok (10%) or Reddit (8%). Notably, TikTok has seen rapid growth as a source of news among younger Americans in recent years.

On several social media sites asked about, adults under 30 make up the largest share of those who regularly get news on the site. For example, half or more of regular news consumers on Snapchat (67%), TikTok (52%) or Reddit (50%) are ages 18 to 29.

While this survey finds that 64% of Americans think the public has become more informed thanks to social media, results of Center analyses do show that Americans who mainly got election and political information on social media during the 2020 election were less knowledgeable and less engaged than those who primarily got their news through other methods (like cable TV, print, etc.).

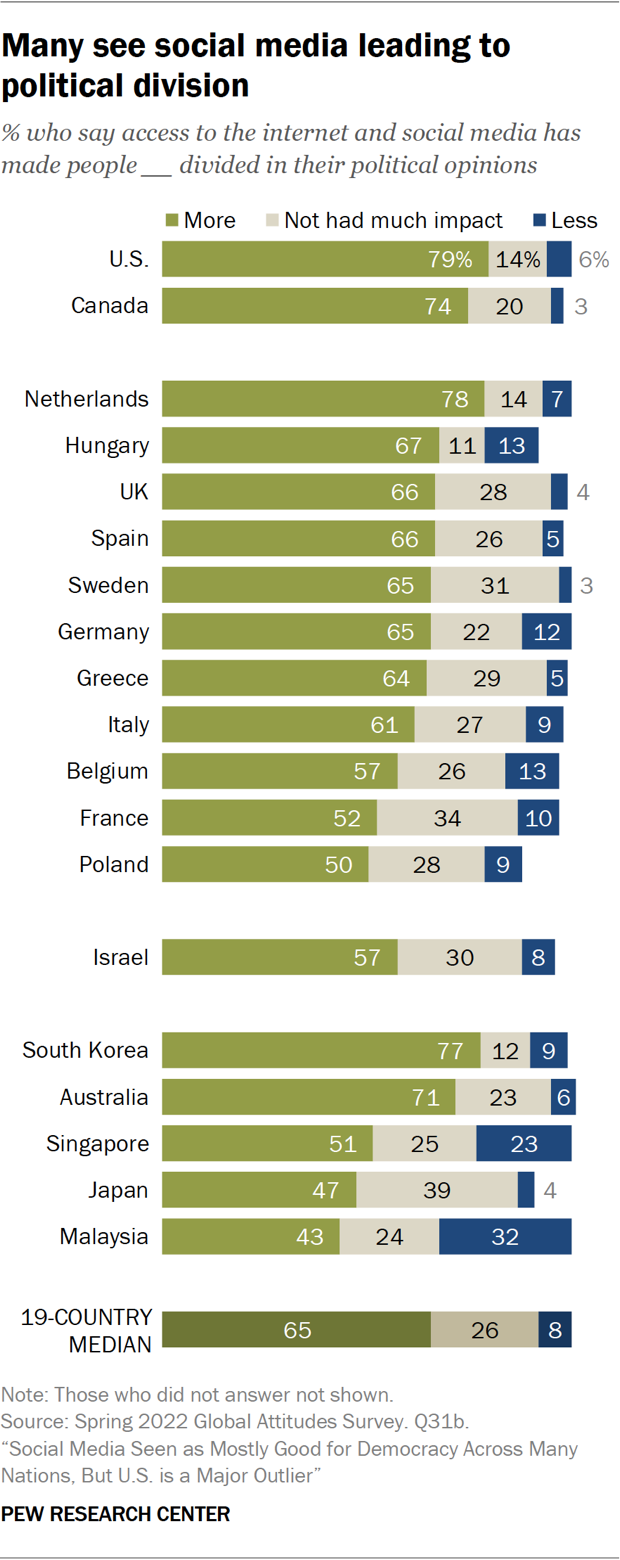

Around half or more in almost every country surveyed think social media has made people more divided in their political opinions. The U.S., South Korea and the Netherlands are particularly likely to hold this view. As a separate analysis shows, the former two also stand out for being the countries where people are most likely to report conflicts between people who support different political parties. While perceived political division in the Netherlands is somewhat lower, it, too, stands apart: Between 2021 and 2022, the share who said there were conflicts increased by 23 percentage points – among the highest year-on-year shifts evident in the survey.

More broadly, across each of the countries surveyed, people who see social division between people who support different political parties, are, in general, more likely to see social media leading people to be more divided in their political opinions.

In a number of countries, younger people are somewhat more likely to see social media enlarging political differences than older people. More educated people, too, often see social media exacerbating political divisions more than those with less education.

Similarly, in the survey of 11 emerging economies conducted in 2018, results of a slightly different question indicated that around four-in-ten or more in every country – and a majority in most places – thought social media had made people more divided.

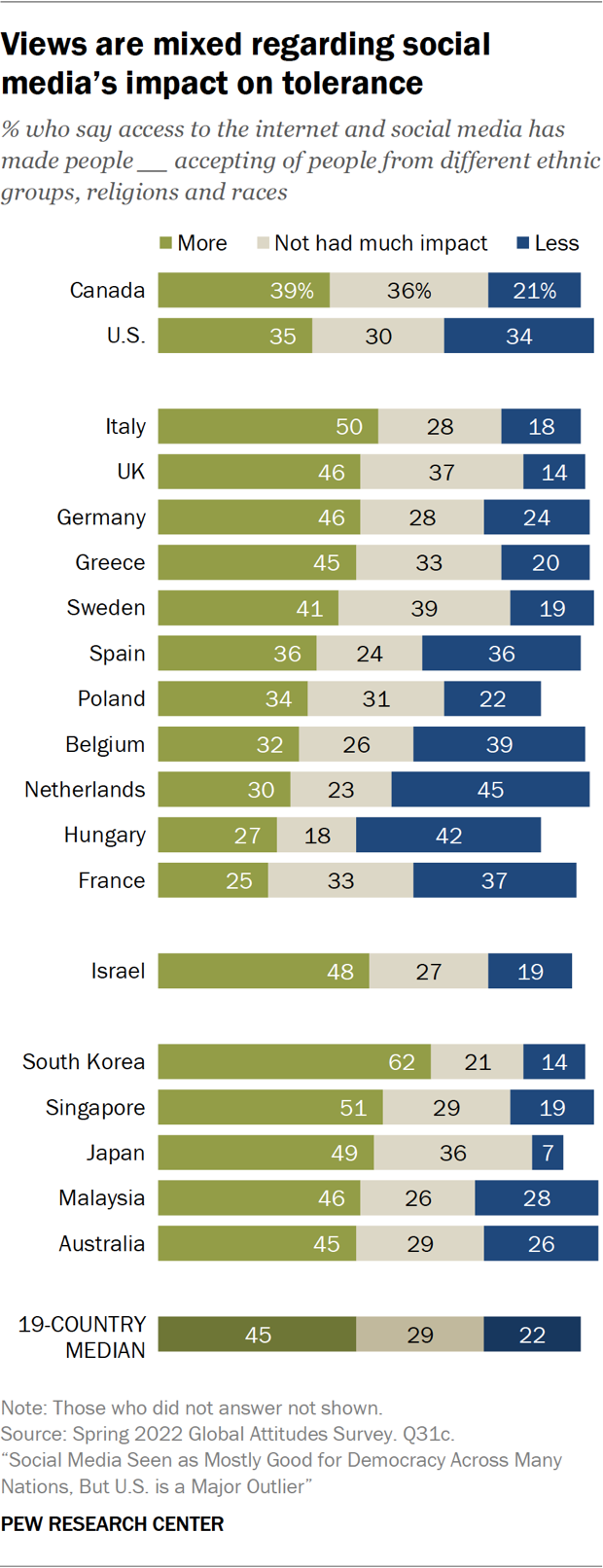

There is less consensus over what role social media has played when it comes to tolerance: A 19-country median of 45% say it has made people more accepting of people from different ethnic backgrounds, religions and races, while a median of 22% say it has made them less so, and 29% say that it has not had much impact either way.

South Korea, Singapore, Italy and Japan are the most likely to see social media making people more tolerant. On the flip side, the Netherlands and Hungary stand out as the two countries where a plurality says the internet and social media have made people less accepting of people with racial or religious differences. Most other societies are somewhat divided, as in the case of the U.S., where around a third of the public falls into each of the three groups.

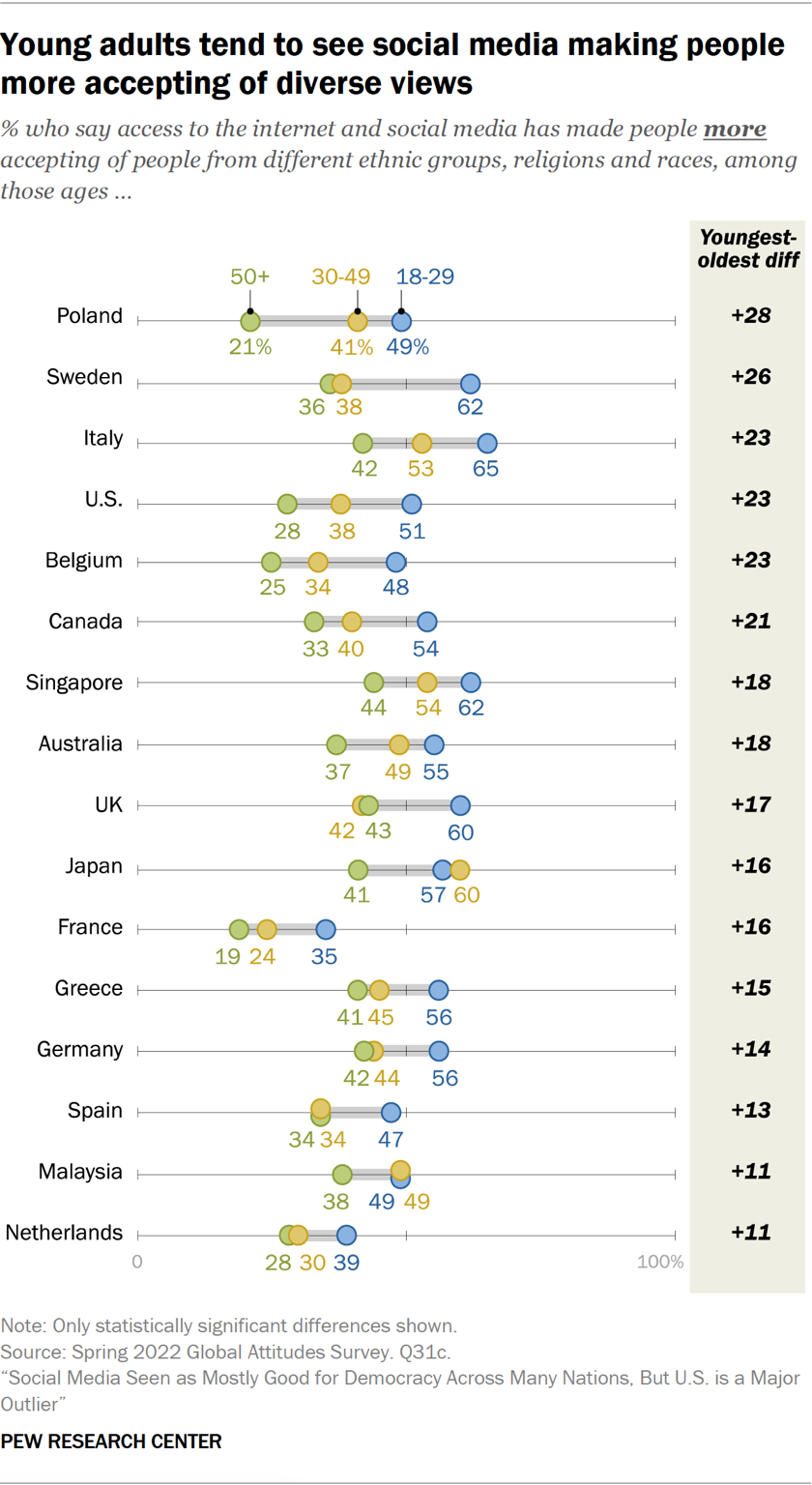

Younger people are more likely than older ones in most countries to say that social media has increased tolerance. This is the case, for example, in Canada, where 54% of adults under 30 say social media has contributed to people being more accepting of people from different ethnic groups, religions and races, compared with a third of those ages 50 and older. In some places – and in Canada – older people are more likely to see social media leading to less tolerance, though in other places, older people are simply less likely to see much impact from the technology.

In most countries, people who see social media leading to more divisions between people with different political opinions are more likely to say social media has made people less accepting of those racially and religiously different from them than those who say social media is having no effect on political division. People who see more conflicts between partisans in their society are also more likely than those who see fewer divisions to place some of the blame on social media, describing it as making people less accepting of differences.

Results of an analysis of the 11-country poll did find that people who used smartphones and social media were more likely to regularly interact with people from diverse backgrounds – though the question did not ask about acceptance, just about interactions. The publics in these emerging economies were also somewhat divided when it came to their opinions on how social media has led to people being more or less accepting of those with different viewpoints.

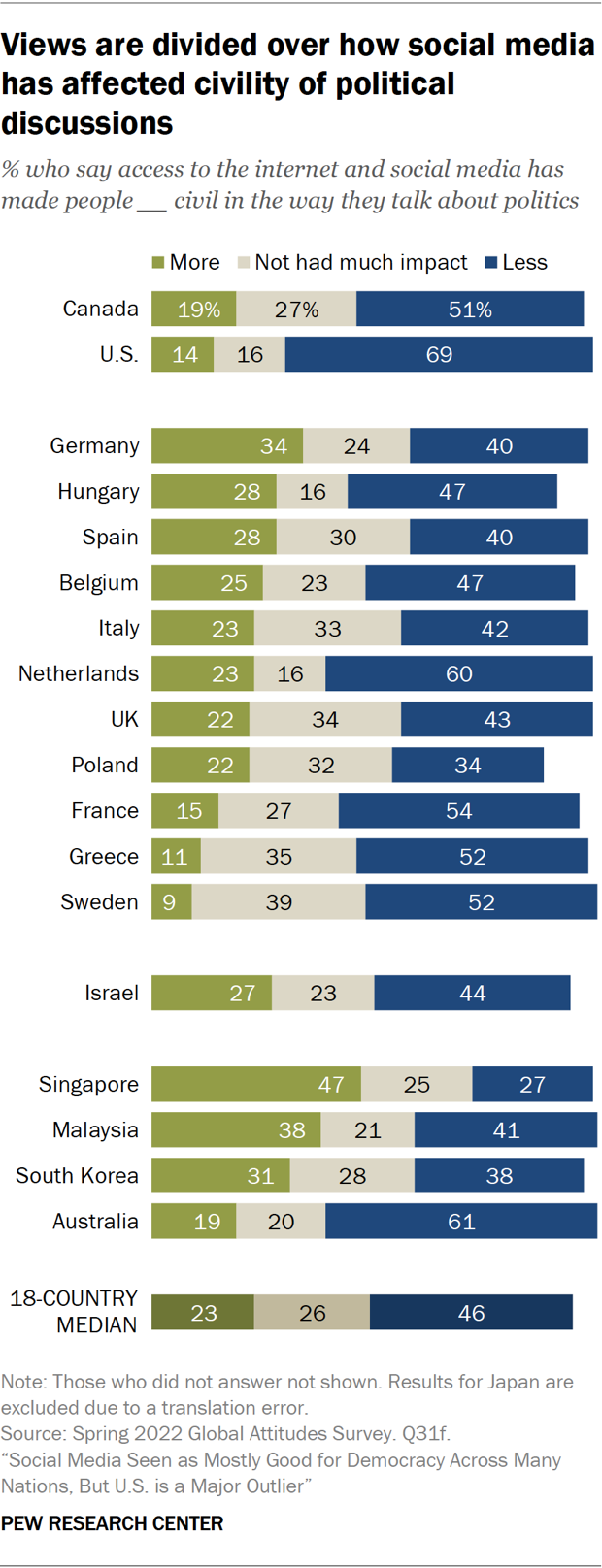

Across the countries surveyed, a median of 46% say access to the internet and social media has made people less civil when they talk about politics. This is more than the 23% who say it has made them more civil – though a median of 26% see little impact either way.

In the U.S., the Netherlands and Australia, a majority sees the internet and social media making people less civil. Roughly seven-in-ten Americans say this. Singapore stands out as the only country where around half see these technologies increasing civility. All other countries surveyed are somewhat divided.

People with higher levels of education tend to see less civility thanks to social media relative to those with lower levels of education.

In most places surveyed, those who think social media has made people more divided politically, compared with those who say it has had no impact on divisions, are also more likely to say social media has made people less civil in how they talk about politics.

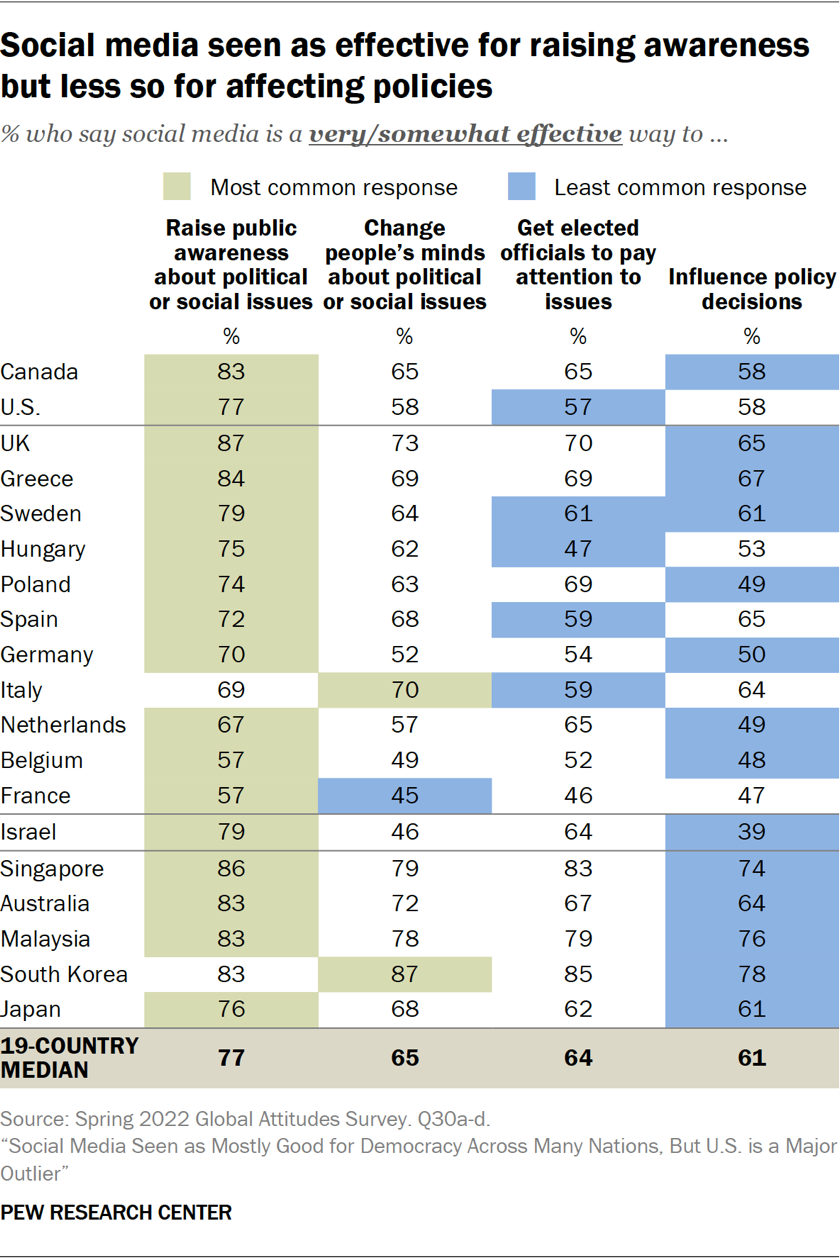

Across advanced economies, people generally recognize social media as useful for bringing the public’s and elected officials’ attention to certain issues, for changing people’s minds and for influencing policy choices. A median of 77% across the 19 countries surveyed say social media is an effective way to raise public awareness about sociopolitical issues. Those in the UK are particularly optimistic about social media as a way of bringing public attention to a topic, with about nine-in-ten holding this belief. People in France and Belgium are the least convinced about social media’s role in raising public awareness, but majorities in both countries still say it’s effective for highlighting certain issues among the public.

Many also consider social media effective for changing people’s minds on social or political issues (65% median). Confidence in social media’s effect on changing people’s minds is strongest in South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia. Germans, Belgians, Israelis and French adults are more skeptical, with no more than about half seeing social media as effective for changing people’s minds on sociopolitical issues.

Views on social media as a way to bring the attention of elected officials to certain issues are similar. A median of 64% consider social media effective for directing elected officials’ attention to issues, and this view is especially prevalent in South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia. People in Belgium, Hungary and France are less convinced.

Somewhat fewer consider social media effective for influencing policy decisions (61% median). Israelis are particularly doubtful of social media as a way for affecting policy change: A majority of Israelis say social media is an ineffective way of influencing policy decisions, and about half in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany agree. About a fifth in Poland also did not provide an answer.

An additional question was asked in the U.S. about social media’s role in creating sustained social movements; roughly seven-in-ten Americans say social media is effective for this. Younger Americans, as well as those with more education or higher incomes, are more likely than others to hold this view. Social media users and those who say social media has been generally good for U.S. democracy are also more likely to believe social media is effective at creating sustained social movements.

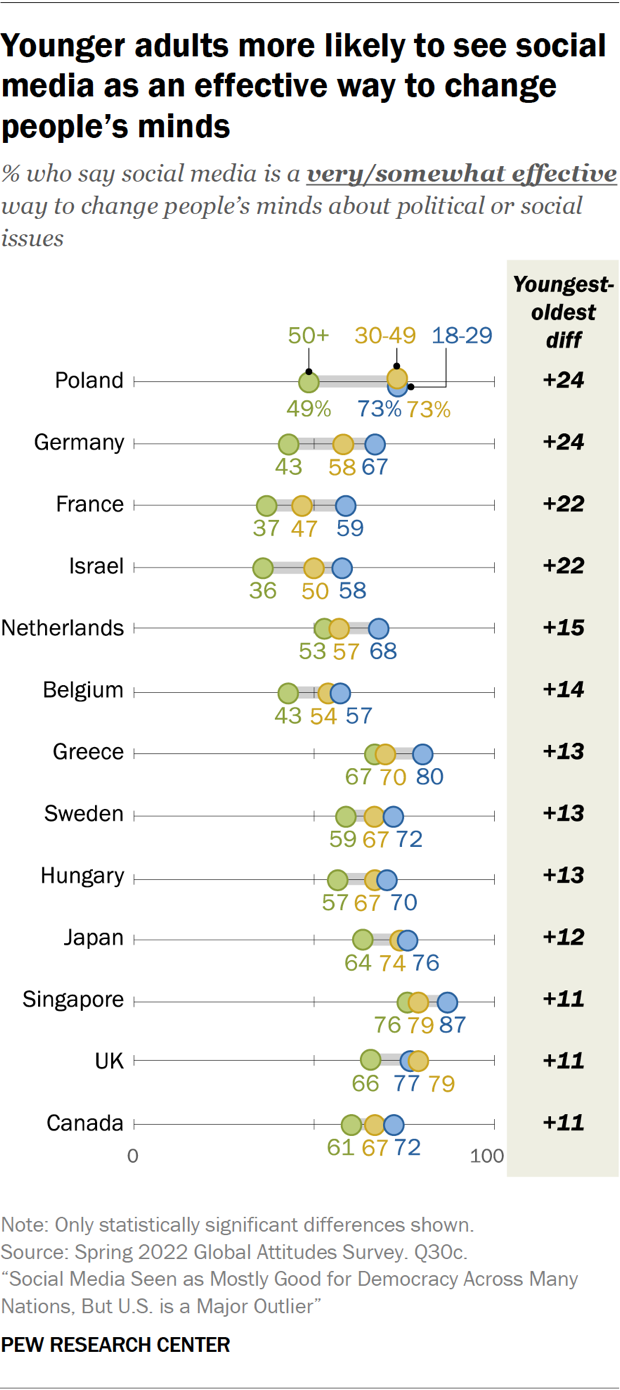

Age plays a role in how people in many of the 19 nations surveyed view social media’s role in public discourse. Those ages 18 to 29 are especially likely to see social media as effective for raising public awareness. For example, in France, 70% of those ages 18 to 29 see social media as an effective way of raising public awareness. Only 48% of those 50 and older share this view, a difference of 22 percentage points.

Similarly, younger adults are also more likely to consider social media an effective way for changing people’s minds on issues. The difference is greatest in Poland and Germany, where younger adults are 24 points more likely than their older counterparts to see social media this way. There are fewer differences between younger and older adults when it comes to social media’s effectiveness for directing elected officials’ attention and influencing policy decisions. Younger adults are also generally more likely to be social media users and provide answers to these questions.

Education and income are other demographic characteristics related to people’s view of social media as a way to influence public discourse. In 11 countries, those with incomes higher than the median income are more likely than those with lower incomes to consider social media effective for raising public awareness about sociopolitical issues. Those with more education are similarly more likely to consider social media effective for elevating sociopolitical issues in the public consciousness in eight countries. People with lower levels of education and income are somewhat less likely than others to provide answers to questions about social media’s effectiveness for influencing policies, changing minds and bringing attention to issues.

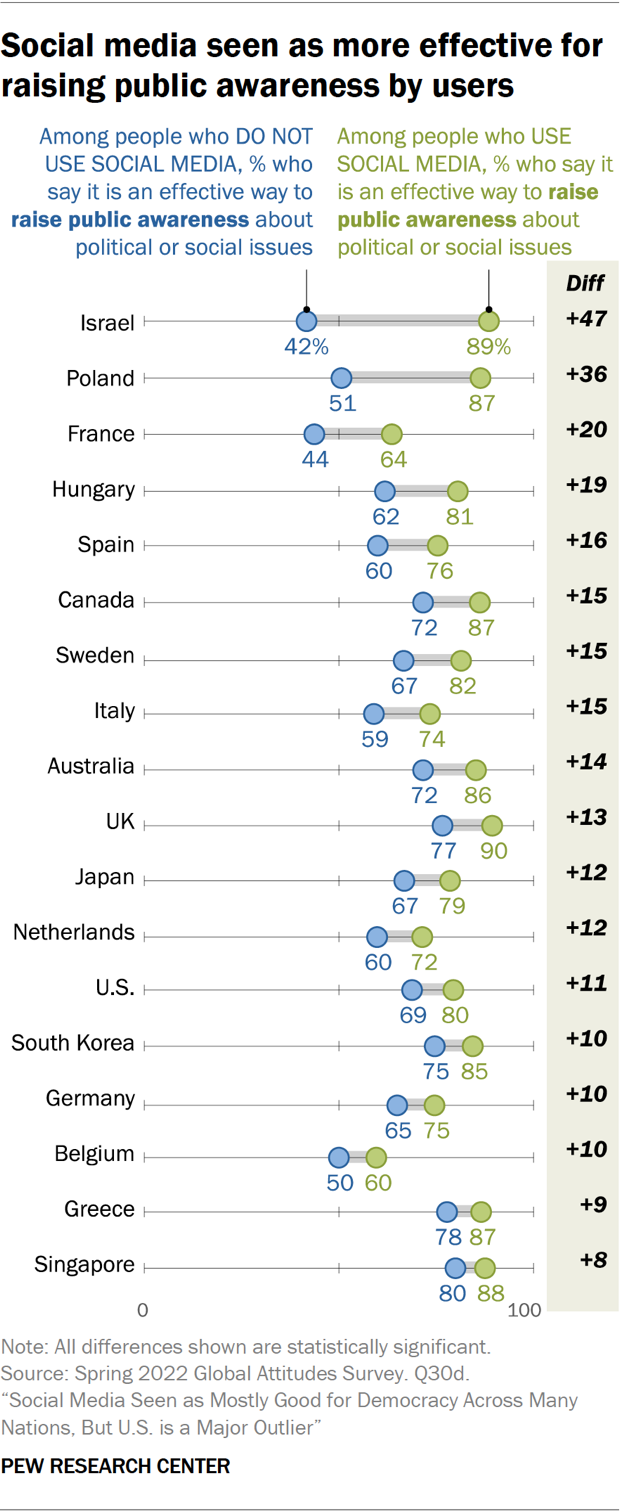

Social media usage is also connected to how people evaluate these platforms as a way to affect public discourse and policy choices. In nearly all countries, social media users are more likely than those who are not on social media to say social media is effective for raising public awareness, and social media users are also more likely to consider social media useful for changing people’s minds in 11 of 19 countries. The differences are greatest in Israel in both cases. Israeli social media users are 47 points more likely than non-users to say social media is effective for raising awareness and 38 points more likely to consider it effective for changing people’s minds on sociopolitical issues. Different views between social media users and non-users are less common when it comes to social media as an effective way for bringing elected officials’ attention to issues or influencing policy decisions. Social media users are also more likely than non-users to answer these questions.

Among social media users, those who are more active are more likely to consider social media an effective avenue for shaping people’s views and attention. Those who post about political or social issues at least sometimes on social media have a greater chance of seeing social media as effective for raising awareness for sociopolitical issues than those who post rarely or never in 16 countries. For example, in Spain, 84% of social media users who post sometimes or often see social media as an effective way to bring awareness to issues, compared to 71% of users who never or rarely post. Similarly, social media users who post more frequently are more likely to see social media as effective for changing minds in 13 countries, for influencing policy decisions in 15 countries, and bringing elected officials’ attention to issues in 12 nations.

People’s views of social media as a way to spread awareness or affect change are additionally related to how they see democracy. The beliefs that social media is effective for influencing policy decisions and for bringing issues to the attention of elected officials or the public are especially common among people who also believe they have a say in politics. For example, in Germany, 60% of people who say people like them have at least a fair amount of influence on politics also say social media is effective for affecting policy choices. In comparison, 43% of Germans who do not think they have a say in politics also think social media can influence policy decisions.