Following three generations of buyback contracts, the new model of Iranian petroleum contracts (IPC) was introduced by the Iranian cabinet to incentivize investments in the country. This paper analyzes the fiscal terms of the contract with technical information from one of the candidate fields for licensing. The financial simulation shows that, in general, the IPC resembles more a service contract than a production sharing contract as the contractor’s take is relatively low—below 5% across different scenarios of crude oil price. Second, the IPC is progressive in that as the overall profitability of the project improves the government takes an increasing share of the economic rent. The results are confirmed in a sensitivity analysis of each party’s profitability and takes on oil price, CAPEX, OPEX and the fee.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Iran has the one of the largest oil reserves in the world. Footnote 1 Traditionally, Iran has relied on buyback contracts for awarding upstream petroleum licenses to international oil companies. A buyback contract is essentially a service contract under which a foreign company develops an oil or gas deposit and recovers its costs and a pre-negotiated remuneration fee from sales revenues, but has no share in the project’s profit. Once the field starts production, the investment is handed over to National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) who will take over the operation of the field Footnote 2 (van Groenendaal and Mazraati 2006). It was first adopted by the Iranian government in 1993. For more than 20 years, the buyback contract was the main apparatus of petroleum licensing in Iran.

Technically speaking, a buyback contract is a type of risk service contract in that all costs are born by the foreign company who can only recover its costs and the agreed remuneration if the field produces at its agreed level and the price is high enough. In other words, the foreign company’s cost recovery and remuneration depends on the field’s performance. The terms of the buyback contract had been revised three times by the national oil company resulting in three generations of buyback contracts (Maddahinasab 2017). Despite these alterations, Iran was not very successful in raising the required investment for its petroleum industry. An oft-voiced critique from international oil and gas companies is that the period of the contractor’s involvement in the field is so short, usually between 5 and 7 years, that Iran’s oil and gas recovery will not be optimized, as the contractor is not incentivized to maximize the long-term recovery. Footnote 3

In order to attract foreign investment to the oil and gas sector, in 2017 the Iranian government introduced a new generation of upstream oil and gas contracts called Iranian petroleum contract (IPC) with more rewarding conditions to foreign investors. In this new framework, the Iranian authorities sought to rectify the deficiencies of the buyback contract. For example, the term of the contract is extended to a maximum of 20 years from the start of development. If enhanced oil recovery projects are to be implemented, the term can extend up to another 5 years and if exploration is included in the contract, then that period will be added to the contract. Footnote 4 The remuneration fee within the IPC framework is based on production rate and set as a fee per barrel of oil or per cubic foot of gas. In contrast, the fee was paid as a percentage of total capital costs under the buyback contract, which could lead to the so-called gold plating. Footnote 5 Elements of progressivity such as an R-factor are also included in the IPC remuneration scheme.

What are the implications of the new IPC framework to investors? Is the fiscal regime under the IPC framework progressive or regressive? To what extent the IPC resembles the traditional buyback contract or the more prevalent production sharing agreement? These questions are the focus of this paper.

Since the Iranian government revealed its plans of setting up a new contract in 2015, a number of papers have analyzed the contract terms, mostly from a legal and contractual perspective, focusing on such issues as the similarities and differences between the IPC, the buyback and production sharing contracts; risk sharing mechanisms, and the progressivity of the IPC. See, for example, Shahri (2015), Ebrahimi and Shahmoradi (2017), Maddahinasab (2017) and Asgharian (2017). Very few papers have focused on the financial implications of the IPC to the investor and the host government with the exception of Soleimani and Tavakolian (2017) and Sahebhonar et al. (2016). Footnote 6 Soleimani and Tavakolian (2017) compare the efficiency of the buyback contract to that of IPC using a number of financial metrics including the government take, the net present value (NPV), the internal rate of return (IRR), discounted payback period and the present value ratio. Although the paper ran several scenarios, it does not give a clear explanation of many of the underlying assumptions such as the capital expenditure, the operating expenditure. It is also unclear why the NPV and IRR of the contractor (in all cases of small, medium and large field) remain almost unaffected when the price scenarios change. Sahebhonar et al. (2016) deal with the financial aspects of the IPC using an Iranian offshore field in the Caspian Sea region, however, since it focuses on a specific type of fields (deep offshore), the generality of its results is limited.

This paper focuses on the financial implications of the IPC to the host government and investors. We calculate the “take” statistic, which shows the division of profits between the host government and the investor over the life cycle of the contract, and analyzes how it changes under different oil price scenarios. The analysis is illustrated using a financial model with technical information from the third phase development of a real oil field located in the South of Iran. The results demonstrate that, in general, the IPC is progressive that as the overall profitability of the project improves the government takes an increasing share of the economic rent. A sensitivity analysis of each party’s profitability and ‘takes’ on oil price, the base remuneration fee, the capital expenditure and the operating expenditure further corroborates this result.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. After the introduction, Sect. 2 describes the fiscal arrangements of the IPC. Section 3 presents the model setup and assumptions for key parameters and scenarios. The results of financial modeling as well as a sensitivity analysis are reported in Sect. 4. Section 5 concludes.

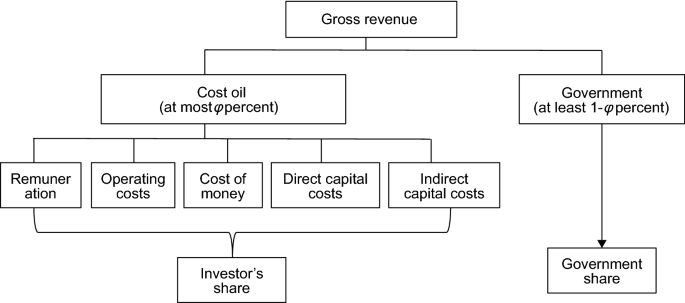

In contrast to the buyback contract under which the investor does not play any role in the production phase, under the IPC the foreign company is allowed to participate in all phases of upstream activities including exploration, development and production. The investor recovers all its accrued costs from the proceeds of oil and gas from the field. In addition, it also benefits from the profit of the field via a per barrel remuneration fee. Figure 1 illustrates the division of the total revenue between the investor and the government. The details of each cost item and the remuneration fee are discussed below.

All costs paid by the contractor will be recovered from field’s proceeds in the form of “cost petroleum.” According to Iranian Cabinet Resolution (2016), the amount of petroleum for cost recovery and payment of the remuneration fee will be capped at a maximum of 50% of crude or condensate and up to 75% of gas produced or equivalent revenues based on market prices. Footnote 8 That is, no more than 50% of oil revenue (75% of gas revenue) from the field can be used to recover the investor’s costs. Unrecovered costs can be carried forward to next year(s).

Direct or indirect capital costs incurred prior to the commencement of primary production will be amortized within 5–7 years from the date when the agreed targeted rate of production is materialized. Capital costs incurred after the primary production will be recovered in 5–7 years from the time of investment.

The remuneration fee is the main mechanism through which the contractor can get a rate of return. Under a buyback contract, the contractor is paid a fixed fee—a fixed percentage of total capital expenditure as agreed in the contract (Maddahinasab 2017). Under the IPC, the per barrel remuneration fee depends on a number of factors including the location of the field, whether the contract covers the exploration phase, the oil price, and how much cost the investor has cumulatively recovered (R-factor). If a field is located offshore or cross the country border, the fee is higher so as to encourage investors to accelerate production. Unlike buyback contracts where the fee is paid within 5–7 years of production, the IPC entitles the contractor to receive the fee from the first or incremental production date until the termination of the contract, which is typically 15–20 years. Table 1 lists the key factors affecting the base fee.

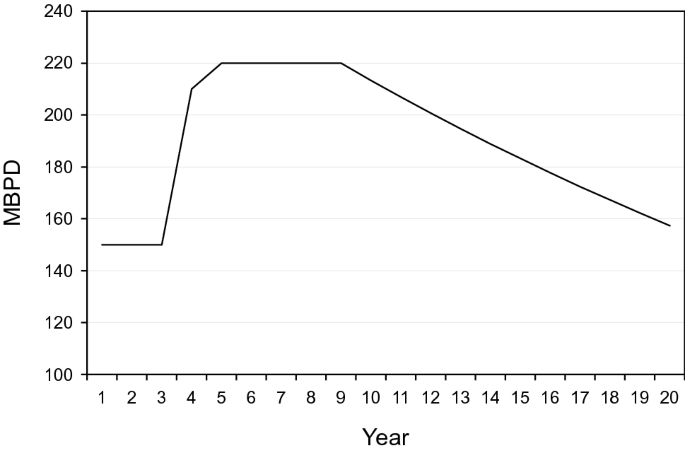

Assumptions for the key economic parameters are summarized in Table 3. For simplicity, all cost figures are expressed in real dollar values. The marginal cost for adding capacity is assumed 15,700 dollars per barrel of production capacity per day, which is reasonable as some of the surface facilities (such as tanks, separators, etc.) are already in place. A $50 million per year of sustaining capital cost is considered for well and facility maintenance and working capital. The OPEX is assumed 6 dollars per barrel, and the cost of money is 6% per year. Indirect capital cost is assumed to be 25% of the total CAPEX. The discount rate is 10% per year, which is the prevalent discount rate usually accepted by international organizations (such as IMF) and international oil companies in their public models. As discussed earlier, the cost recovery cap is set at 50% of the annual proceeds for crude oil.

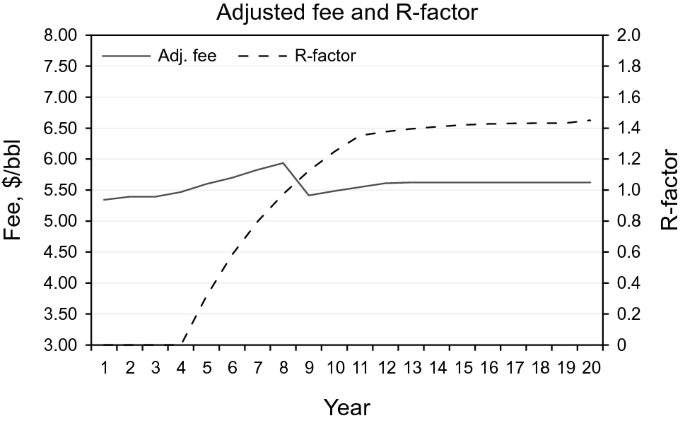

As discussed in Sect. 2, the investor’s remuneration fee is determined and adjusted on the basis of oil price and R-factor. Based on our communications with senior officials of the NIOC, we consider a base remuneration fee of $5/bbl with a corresponding Iranian exported crude oil price of $60/bbl. With regards to the R-factor adjustment, the per barrel remuneration fee decreases as the R-factor increases. Figure 4 plots the R-factor along with the adjusted fee in the reference case. The adjusted fee drops between Year 8 and Year 9 because the R-factor reaches 1.0, and the fee is adjusted to 90% of the base fee.

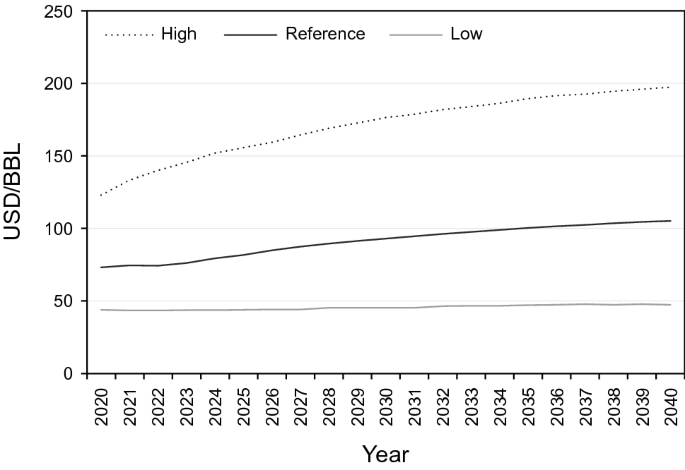

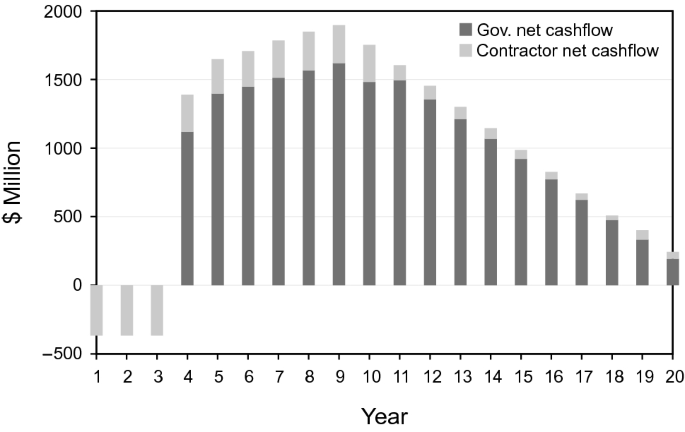

Given the above assumptions about oil prices, cost structure, and production profile, we compute the internal rate of return (IRR), net present value (NPV) both for the project as a whole and for the investor and government, respectively, under different price scenarios.

Table 5 reports the main results of the simulations for all price scenarios. For each price scenario, we compute the IRR for the project as a whole and for the oil company, the NPVs, respectively, for the project, the oil company and the government. To examine the effect of discount rates on the net present values and takes, we compute both the undiscounted NPVs and the discounted NPVs assuming a 10% discount rate.

Our last exercise is to examine the sensitivity of each party’s profitability and takes on changes in oil price, CAPEX, OPEX and the fee. To fix ideas, we use the flat price scenario as the base case for sensitivity analysis. Recall that in the flat price scenario the oil price is fixed at $65/bbl throughout the contract period. This helps us isolate the effect of price changes over time from changes in other factors. For each sensitivity case, we vary the parameters of interest, i.e., oil price, the fee, CAPEX and OPEX, from their base case by 50–200%, while holding other parameters constant from the base case.

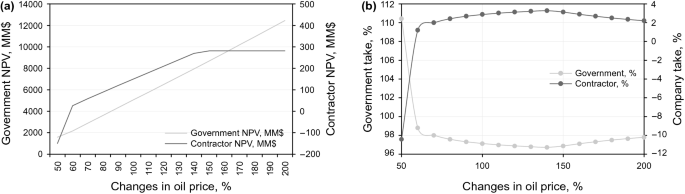

The sensitivity of each party’s net present values and ‘takes’ on changes in the benchmark oil prices is depicted in Fig. 6. As the benchmark oil price (Brent) varies from 50% to 200% of the base case ($65/bbl), both the government and the contractor’s NPVs increase. Because of the kinks built in the fee adjustment formula, the contractor’s NPV grows quickest when the oil price is below 60% of the base case and flattens when it is above 150% of the base case. In comparison, the government NPV is almost linearly increasing as oil price increases.

Figure 6b shows the sensitivity of the ‘takes’ to changes in the oil price. If the benchmark oil price is 50% of the base case, i.e., $32.5/bbl, then the contractor has a negative NPV and therefore a negative ‘take.’ As the oil price increases, both the contractor and the government NPVs increase. Because the contractor’s remuneration fee is capped when the oil price is above 150% of the base year oil price and because the fee is adjusted to 0.9 from 1.0 as the R-factor crosses the 100% threshold, the share of company’s take declines when the oil price is higher than 150% of the base case crude oil price.

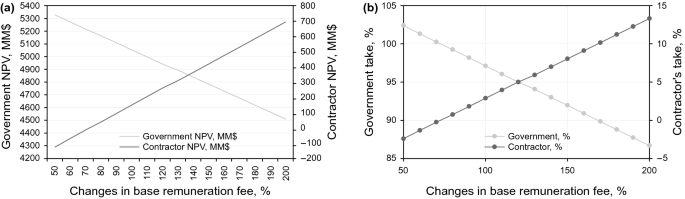

When the base remuneration fee increases, the NPV of the contractor increases and that of the government decreases (Fig. 7a). Figure 7a also indicates that when the base remuneration fee falls below 80% of the assumed base fee of $5/bbl, the NPV of the contractor becomes negative. Similarly, as the base remuneration fee increases, the contractor’s take increases and that of government decreases (Fig. 7b). The remuneration fee is the main mechanism through which the contractor can obtain a share of profit. As the base remuneration fee changes, the contractor’s NPV and its share in the total project NPV change linearly in correspondence to the fee change.

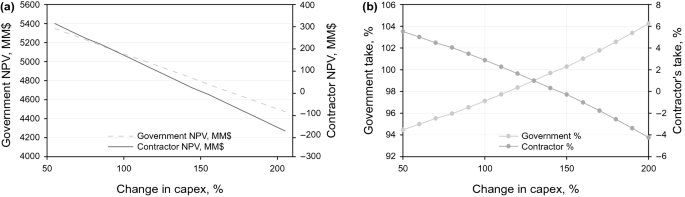

The sensitivity of both parties NPVs and takes to changes in the capital expenditure is depicted in Fig. 8. Not surprisingly, as the capital expenditure increases, holding other things constant, both the government and contractor’s NPVs decrease (Fig. 8a). The ‘takes’ depicted in Fig. 8b, on the other hand, show that as the capital expenditure increases (i.e., the total profitability of the project decreases) the government takes an increasing share of the discounted profit from the project while the contractor’s ‘take’ is declining. This is primarily due to the effect of discounting. Recall that the capital expenditure incurs in the development phase which is in the early years of the contract. The cash in-flow of the company (contractor) depends on the repayment of capital cost Footnote 12 and the remuneration fee, both of which only occur in the production phase. As the benchmark oil price is fixed, the remuneration fee per barrel is largely fixed and the total remuneration accruing to the contractor changes with the production profile. Thus, if the CAPEX increases, it has a larger impact on the contractor’s net present value than on that of the government.

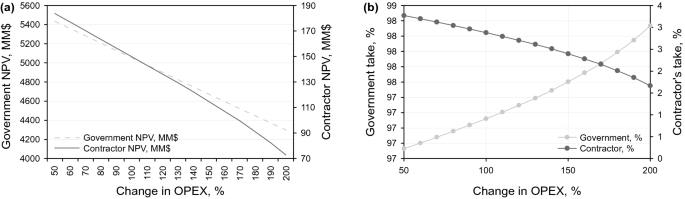

Figure 9a, b depicted the sensitivity of the parties NPVs and takes to changes in the operating expenditure. The pattern is similar to the sensitivity of CAPEX exhibited in Fig. 8. As the OPEX increases, holding other things constant, both the government and the contractor’s NPVs decrease (Fig. 9a). Similar to an increase in CAPEX, an increase in OPEX leads to a declining share of the contractor’s take and increasing share of the government take due to the discount rate effect.

In sum, the sensitivity analysis indicates, in general, as the profitability of the project improves, the government takes a larger share of the profit. Thus, the fiscal regime under the IPC is generally progressive rather than regressive.

This paper analyzes the fiscal regime under the new Iranian Petroleum Contract which evolves from the traditional buyback contract. There are both similarities and differences between the IPC and the buyback contract. Like buyback contracts, the contractor under the IPC regime recovers its direct and indirect capital cost, operating costs, banking costs and remuneration from the proceeds of the field. There are three differences between this contract and buyback. Firstly, there is no limit for CAPEX when the contract is signed. Secondly, the contractor’s remuneration is not fixed and depends on the production level and R-factor which is similar to Iraq’s service contracts. Thirdly, the term of the contract is extended to the production phase to incentivize the contractor for long-term behavior.

A financial model using technical information from the third phase development of an oil field located in the South of Iran is developed. There are two key results from this exercise. First, across all price scenarios, the contractor’s ‘take’ is relatively low—below 5%, indicating that the IPC resembles more a service contract than a production sharing contract. Second, in general the IPC is progressive in the sense that as the overall profitability of the project improves the government takes an increasing share of the economic rent. A sensitivity analysis of each party’s profitability and takes on oil price, CAPEX, OPEX and the fee corroborates the result.

Our analysis has profound policy implications for both the investors and the host government. First, although the IPC has introduced a number of changes to the contract term, CAPEX allowance and remuneration that could be welcomed by investors, the contractor’s take under the IPC is not much different from traditional service contracts and is unlikely to prove effective in attracting foreign investment. Second, since the remuneration fee is the main mechanism through which an investor can obtain a return, it is important that the investor negotiates a favorable remuneration fee. Third, our sensitivity analysis indicates that the government take is more sensitive to the fee, capital expenditure than the operating expenses. Thus, the hosting government must focus on the fee and the CAPEX rather than operating expenses in contract negotiations. On the other hand, if the government aims to improve the overall profitability the project hence the rent, they should also target capital expenditures instead of operating costs.

For future research, there are a number of avenues that this analysis can be extended. First, it would be useful to study the investor’s optimal behavior using a dynamic model where the investor’s investment and production decisions can be modeled as choice variables in response to the oil price, the remuneration fee and other contractual factors. Such a model could provide additional insight on how the contractual arrangements influence an investor’s behavior. Second, given the significant uncertainty in the oil price movement and other technical parameters such as the production rate, a stochastic simulation with the key variables would help quantify the range of possible outcomes and aid decision making for both the contractor and the hosting government under uncertainty. Footnote 13 Lastly, it would also be interesting to incorporate the technical aspects of the field into the financial modeling. Footnote 14 Since the contractual parameters (such as the fee and its sliding scale) vary with field technical difficulty, a model integrating the technical parameters of the field with contractual parameters could provide more accurate estimate of the contract implications.

According to BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019, Iran’s proved oil reserve is ranked 4 th in the world after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Canada. However, if we exclude Venezuela’s heavy oil from the Orinoco belt and Canadian oil sands, Iran is the second largest country in oil reserve, next only to Saudi Arabia.

Once the field reaches the targeted rate of production—which is agreed upon by the parties- and can keep for 21 days out of a period of 28 consecutive days, the foreign company will hand over the operation to NIOC.

In this paper, the word ‘investor,’ ‘contractor, and ‘foreign company’ will be used inter-changeably.

According to Clifford Chance (2017), the term of contract is up to 26 years, including 4 years for exploration, 2 years for appraisal and up to 20 years from the start of development operations. If necessary, it can be further extended by up to 7 years (2 years for the exploration phase and 5 years for enhanced oil recovery).

In taxation, “gold-plating” refers to the attempts by companies to inflate costs through overspending on projects.

In addition, a number of papers have analyzed the optimal production rate and efficiency of risk service contracts. For example, see Luo and Zhao (2013), Ghandi and Lin (2012), and Ghandi and Lin Lawell (2017).

LIBOR: London interbank offered rate which is a benchmark interest rate at which major global banks lend to one another in the international interbank market for short-term loans.

The base price is assumed $60/bbl. - The name of the field is removed due to confidentiality limitations. In the low price scenario, the adjusted fee ranges $3.76–3.86 per barrel from year 9.Recall, the capital cost is amortized over a period of 7 years from the time when the daily production rate reaches a certain threshold.

For a stochastic analysis of upstream petroleum contracts in China see Hao and Kaiser (2010) and Liu et al. (2012).

See, for example, Park et al. (2009) in which a combination of technical factors, such as reservoir properties and well production rate and economic parameters, such as price, are analyzed in an integrated model to study the impact of uncertainties on petroleum developments.